Collecting Life by Davis Smith

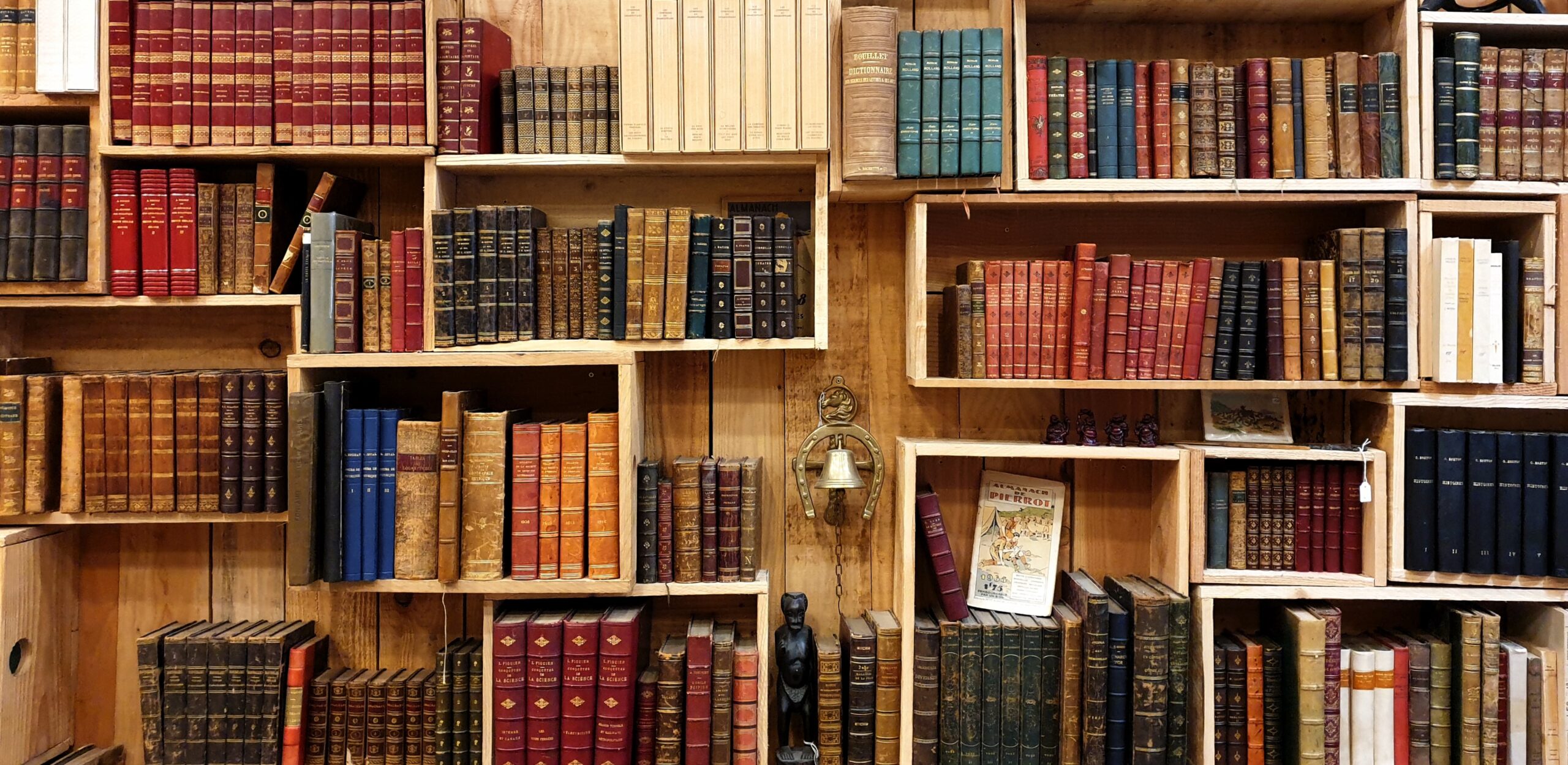

Ideas can be easy enough to conceptualize, but they can be frustratingly isolated from the routines of life as it is actually experienced. We learn in the classroom, in church, through conversations with friends, yet life demands concrete results, and often we are left struggling to merge the abstract with the concrete. We ought rightfully to detect strains of heaven in all created things, to live always with the knowledge of spiritual presence. Yet we are Thomases all; creatures who demand physical signs of even the most primal and necessary realities. Thankfully, Christ will never hesitate to thrust our fingers into His warm wounds or pull us through a purging fire of grace. Art and nature are the two great physical books of ongoing revelation, but one also needs incarnational anchors in the home to continually stand as a consoling presence in all seasons and a point of starlight in the midst of the mundane that reminds us to embrace the miraculous. I contend unabashedly that curating and maintaining a personal library is one of the most effective means by which to fill this gap. The only reason to keep a library is if you believe that the discipline (I do not hesitate to call it such) has meaning beyond the mere sight of the objects on the shelves, the aged splendor of love-worn pages and the soul-ballooning scent of fermented knowledge emanating from the spines. If not, then the collection becomes nothing less than a hobby farm that loses all its fragrance and triumph when the paper eventually disintegrates and one is no longer alive to handle it. We must view libraries as repositories of loveliness. Their essence must be wrapped up in duty rather than wantonness. They must bury roots in the soil of the soul rather than blow around arbitrary spores. When anger and bitterness mars my day, when evil flutters around my mind and launches torpedoes toward my mind, when “it is a damp drizzly November in my soul” and “it requires a strong moral principle to prevent me from stepping into the street and methodically knocking people’s hats off” (to quote Herman Melville’s Ishmael in Moby-Dick), I run to my shelves and the treasury that they upholster. The purpose of literature, according to T.S. Eliot, is to turn blood into ink. The purpose of a library, then, must be to ceaselessly offer up its inky, papery riches as a feast to be absorbed into the bloodstream and shuttled off to every extremity.

“Art and nature are the two great physical books of ongoing revelation, but one also needs incarnational anchors in the home to continually stand as a consoling presence in all seasons and a point of starlight in the midst of the mundane that reminds us to embrace the miraculous. I contend unabashedly that curating and maintaining a personal library is one of the most effective means by which to fill this gap.”

Though I cannot remember a time when my favorite pastime was not to be sprawled across the couch with a book cradled between my hands, I have now had about nine years of library-curating experience, and like any semi-experienced practitioner, I feel the need to lay out Four Rules for the practice. Whether you’re interested in taking the leap of faith necessary to begin your collection or you need to reform your gluttonous or anemic habits, here are a handful of truths in which the business of library-crafting has schooled me. Before this, a clarification: library-keeping is not inherently worthier than gardening, cooking, family-raising, community-serving, friend-fostering, music-listening, poetry-writing, or weightlifting. But it belongs in the same category as all those in that it mingles the commonplace with the sublime. We should try our hand at all these things at some point, and I hope that you can apply my paeans here to any everyday craft you may engage in.

4. Segment your library, or it will become a gelatinous mush.

I do not mean merely the act of physically sequestering your books, which may satisfactorily be executed in any number of fashions. Rather, I mean that any library should consist of several sub-libraries or collections. This helps you to keep each species of knowledge where it belongs in the endeavor to create a properly-ordered Platonic state out of your books. This does not mean that you cannot make connections across your collections. However, to put this maxim crudely, Treasure Island and Augustine’s Confessions both belong in any library worth its salt, but ought they to occupy spaces next to each other on the shelf, and ought you to devote equal time to studying them? As for me, I mentally sort my books into four different collections which I consider before making a purchase and when taking stock:

1. The Main, or Great Conversation Collection. I organize these chronologically, from the Epic of Gilgamesh to contemporary fiction. These are the undisputed Great Texts of civilization, containing the major ideas that have contributed to the development of our culture. This should form the undisputed centerpiece of a library. Here resides your Chesterton and your Charmides, your Plutarch and your Proslogion, your Sophocles and your Solzhenitsyn. Get to know these better than the back of your hand—treat them like family members. This collection is the Parnassus dominating the landscape of your library, and it should always be your top priority to nurture.

2. The Reference Collection. In addition to the primary texts in the Main Collection, one should collect various viewpoints—old and recent—on history, literature, theology, philosophy, the sciences, etc. These are of use for research projects, background reading, and the like. However, never let it rival the size of your Main Collection! Keep C.S. Lewis’s advice about reading old books in mind (also, keep C.S. Lewis on your shelves). For every commentary on Dante that you add, add another translation of Dante, for every book on the Reformation, another anthology of Luther’s works, etc.

3. The Lollipop Collection. One would be a miser indeed who lacked one of these, and anyone who tries to talk you out of curating this collection should be disregarded until the three ghosts of Christmas have slapped some sense into them. In this tiny but delightful wedge of my library sits such fare as Norton Juster’s The Phantom Tollbooth, William Goldman’s The Princess Bride, Jerome K. Jerome’s Three Men in a Boat, and Arthur Conan Doyle’s complete Sherlock Holmes stories. You should try to read one of these about once every two months to keep the juices in your brain from getting stagnant. I like to look at them as bonbons, which I use as tasty palate-cleansers, but which it would be daft to make an entire meal of.

4. The Specialty/Personal Enthusiasm Collection. The other three categories comprise the books that you should collect. Here is the one collection where you get to embrace your idiosyncrasies. I personally believe that buying antique books for sheer aesthetic appeal is overrated, but some can’t get enough of it. Conversely, I do love finding very old books that aren’t in print anymore or which have been otherwise consigned to oblivion, even if they aren’t necessarily the kind of books I would otherwise pick up. Family heirlooms and the like also belong here. But only focus on personalizing once you’ve got the hang of standardizing.

3. Be ruthless about culling.

Like all our undertakings, the practice of book collecting can be marred by undue avarice, excess, and egotism. Once a year or so, your library needs to be purged of dross. By adhering to this custom, you will never succeed in purifying it entirely, but you will be taking an important step in your vocation to tend the garden of creation. Plus, like exercise, painful as it can be, it makes you feel better when it’s all done and over with. Cull all volumes that repeat or restate other material. If you haven’t slipped a book from the shelf in over a year, free it from its dust-encrusted prison and examine it. Does it have the potential to bring joy? (By the way, as long as we’re on the subject, have you ever removed all your books from a shelf and looked at what’s underneath? If you don’t want to have your next reading experience ruined by disturbing fuzz-like objects that apparently generated through abiogenesis, make the effort to dust every once in a while). If you keep something around just for sentimental value or you can’t give a concrete reason for your desire to keep it besides “I like it,” then consign it to the Goodwill bin.

2. Never be content with predictability.

Just because you’re a devotee of theological exploration doesn’t mean you need to focus only on buying up all the doorstopper Systematic Theologies. Any field of inquiry that can’t be related to another is not a worthwhile one for your time. Look for theology in novels, poetry and drama, scientific writings, and essays from all time periods. When your visitors and loan candidates (what, did you think anyone who wants to “borrow a book for a while” is equally eligible?) question why you have Cormac McCarthy next to Wendell Berry, and Karl Marx next to Cardinal Newman, tell them that you are unafraid to sniff for truth in all its outfits, and to own every book that fancies itself a serious description of our condition for fear of whizzing past an epiphany like a Porsche past Big Sur. Conversely, if you’re a fiction buff, populate your shelves with expository works. They will help you explicate the stories you digest, and assimilate all forms of thinking into one. Cultivating unpredictability can also take the form of deciding to put down your expected purchase of a lush volume of Tolkien in favor of a tantalizing work from an author you’ve never heard of. Make bold decisions every once in a while. Your soul will thank you.

“Cultivating unpredictability can also take the form of deciding to put down your expected purchase of a lush volume of Tolkien in favor of a tantalizing work from an author you’ve never heard of. Make bold decisions every once in a while. Your soul will thank you.”

1. Stock your library like you’re stocking your refrigerator.

Anyone who packed their fridge to the gills with so many provisions that the produce drawers refuse to shut and four (!) different kinds of milk line the top shelf needs professional help or anti-conspiracy-theory counseling. One would hardly call such a person a food enthusiast. Conversely, one should seek an appropriate level of richness and variety. Thus, there are library gluttons and anemics. The true gourmet is unhesitant about plucking all glistening fruits, experimenting with all techniques, having any ingredient on hand to accompany a sudden rush of inspiration. But he never hoards and stuffs himself, or underprepares and undereats. How a man’s bookshelves are stocked, there his heart will be also. The gross accumulation of books for the sake of acquisitiveness or wanting to “learn as much as you can” is shameful. But so, too, is the rejection of anything with the potential to surprise or invigorate you when you least expect it. Only put into your mind what is good. Sample much, collect a decent amount, cull what offends the appetite for beauty. Above all else, learn about what it means to be human from everything you own and read. Spit out the rancid fare, stock up on the fresh stuff, enjoy sweets in moderation, revel in abundance. Pursue the golden mean, for it means nothing less than the universe. Taste and see that the Lord is good, and that all His promises are sweeter than honey and fine gold. For every good book contains the promise of that “life beyond life” spoken of so rapturously by Milton in his Areopagitica. Indeed, every well-tempered library is a collection of life, for, according to Milton, “books are not absolutely dead things…a good book is the precious life blood of a master spirit, embalmed and treasured up on purpose to a life beyond life.” Feast on the fecundity of signs, smash all your gnostic leanings with the sledgehammer of incarnational knowledge. Heaven hangs on the threshold of earth, dropping paper and ink as covenant manna. Freely create, curate, and absorb; even as you tread continuously closer to that for which all the world is made.