Making a Mess: Some Thoughts on Craft, Instinct, and George Saunders by Lissa Torres

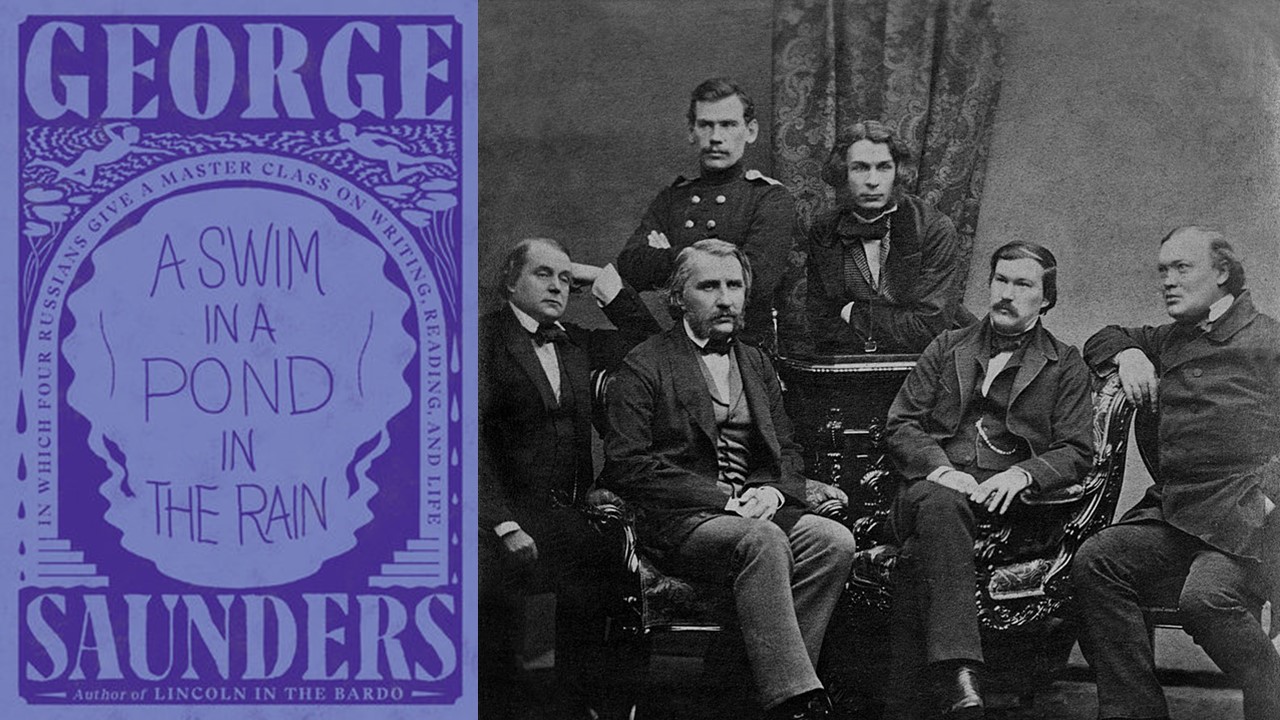

When was the last time a craft book was on the New York Times Bestseller list? Not sure, apart from George Saunders’ A Swim in a Pond in the Rain (2021). The book takes several classic Russian short stories and considers them from a writer’s perspective—how are they built? What keeps readers reading? These are stories Saunders has been teaching for years, so his thoughts have been sharpened by years of examination and discussion. To read this book, therefore, is the next best thing to actually taking a class with Saunders—which, for those who’ve read Saunders’ own fiction, full of humor and humanity, sounds like a dream.

I can’t remember the last time I was so excited to dive into a book. (Get it?)

Short fiction is not a genre I typically work in, so I took the reading of Saunders’ book as a prompt, or an excuse, or directive—to try my hand at the short story again, especially utilizing and in light of what is discussed in Saunders’ book. A self-directed study, if you will. The Russian stories would be course texts. Saunders would be my instructor. My final project would be to write a short story. (Can you tell I miss being a student?)

***

Saunders begins with a page-by-page reading of Chekhov’s “In the Cart,” explaining some ground rules for short fiction along the way. A story, as Saunders describes it, begins from characterization, and plot (or “meaningful action” as Saunders prefers) proceeds out of that characterization. From the first page, Chekhov creates “certain expectations” that are rooted in what we learn about Marya’s character, and readers will find “the rest of the story to be meaningful and coherent to the extent that it responds to these” (14).

If we learn at the beginning of a story that a character has never been afraid, we expect that in the story he will encounter fear. If instead we learn a character lives to avoid embarrassment, we expect the character will find himself in just the sort of situation he’d prefer to avoid. Character, built through “increased specification,” is the origin of meaningful action. The more we learn about a given character, the more the path of meaningful action narrows. If what we learn about a character does not direct the action of the story, why is it there? Short stories, Saunders reminds us, are brutally efficient. They do not waste time with details that are not useful to the story.

By the middle of the book, in considering Chekhov’s “The Darling,” Saunders has built a series of “laws” for fiction: “Be specific! Honor efficiency!…Always be escalating” (153). He’s explained the importance of cause and effect driving the action of a story in order for that story to emerge as meaningful (147). He concludes his consideration of “The Darling” with this idea that I’ve still been thinking about, days after reading it: “The more I know about [a character], the less inclined I feel to pass a too-harsh or premature judgment. Some essential mercy in me has been switched on. What God has going for Him that we don’t is infinite information. Maybe that’s why He’s able to, supposedly, love us so much” (160).

“The more I know about [a character], the less inclined I feel to pass a too-harsh or premature judgment.”

George Saunders

This is quintessential Saunders: specificity and fully imagined characters lead to more humane stories. The more we know of a person, the more compassionate we are towards them. The more we care about them. The more we’re willing to forgive, and the more we’re willing to empathize. This is one of the essential values of fiction—that it shows us something about each other, and in reading fiction, we’re also learning something about “reading” each other.

***

Armed with fresh zeal, I went to work at getting a first draft of my own story down. It was uncomfortable. My genre of choice is the personal essay, and at this point I’ve collected a bank of material I can draw on when I sit down to the page, ephemera I’ve gathered for just such occasions, tidbits I’ve saved for a rainy writing day.

I have no such commitment to and therefore bank of ideas gathered for fiction. I had to…make stuff up? Out of what? I slowly, awkwardly, got a character down on the page. Elise is trapped in the domestic, finding herself watching Grey’s Anatomy to distract her from the mindlessness of caring for a young child. At various points, Elise reflects on her past, the series of events that led her to make a choice to be a mother.

She felt suspiciously like myself. Minus, you know, the “trapped” bit.

But there were other cool images and moments that came through that I was interested in—an obsession with mirrors, a talking teapot, a scene from Grey’s Anatomy where two characters draw a tumor on the wall. The ending felt the shakiest, but isn’t that always the problem with short fiction? Sticking the landing. That’s what revision is for. That’s what, I thought, Saunders would help with.

I wrote the draft so that I could take notes as I read Saunders regarding what I should do to revise the story. I made marginal notes on my draft tied to specific pages from Saunders. (Always be escalating!) I was daunted but enthusiastic in my quest, gathering up instructions from my instructor.

***

Then, I read “Afterthought #3” with horror, the unique sort of bottom-of-the-pit feeling you get from realizing you made a mistake when you really should have known better. Saunders intersperses these “afterthoughts” among the stories and chapters, handful-of-pages-long reflections on writing and the writing process. In Afterthought #3, he writes, “A plan is nice. With a plan, we get to stop thinking. We can just execute…. Having an intention and then executing it does not make good art. Artists know this” (161).

The whole time I’d been merrily making notes on my draft—need pivot here—need escalation here—I’d been ignoring a nagging voice in the back of my head that told me those notes weren’t going to be that helpful. For one thing, I just don’t write that way—planning things out, essentially outlining (unless it’s a piece of academic writing—a different ballgame). For another, even if I did, I don’t think what I’d produce would be much worth reading. I’d just been so swept up by the potential of the project—reading and writing alongside Saunders—I’d ignored its flaws.

I have this memory from grad school of hanging out in the TA lounge and overhearing a conversation between two aspiring writers. One was despondent, sure her final project for workshop was going nowhere. The other was trying to encourage her, but was told, “But you’re an artist. I’m not.” The comment was baffling. I thought, You are literally in a Master of Fine Arts program. How can you say you’re not an artist? Then I wondered—What does she see as being different between what her friend is doing and what she’s doing? And also: What makes a piece of writing art? The story has stayed with me, and I’ve wondered about what artists do—the process of artistry—and how that compares with a study of or competence in an art form.

In Afterthought #3, Saunders essentially confirms what I’ve come to believe from experience—that a story or poem or essay (even a competent one) does necessarily register as art. I can’t plan my way to art. Can anyone? Perhaps. I certainly can’t presume to rule it out. But when I think of my own process, I find myself in the Saunders camp. I write my way to art. (Or revise my way to art.) Nicole Walker said it this way: “Words beget words.”

“Words beget words.”

Nicole Walker

I teach creative writing, and so this is a question I come back to over and over again. How does one teach another to be an artist if artistry ultimately embodies a tension or meaning that can’t be fully articulated? If, by its nature, art moves beyond some sphere of explainability? We spend all this time in class examining good writing, taking it apart at the craft level, and drawing conclusions about how craft works. This is what Saunders is doing in A Swim in a Pond in the Rain, what I’m trying to do as I read his book. What are we hoping is going to happen?

The conclusion I come to most often is that a study of craft leads to better instincts as a writer. And there, I said it—instincts. Because at the same time I’m offering my students tidy tips (as Saunders was offering me—be efficient!), I’m also telling them to just sit down and write and not worry where their writing goes. Follow the weirdness, follow the gut, follow the instincts. Let loose. Make a mess.

I was not allowing this of myself in my short story. I was attempting to control every aspect of the craft and the direction of the story without letting myself discover the story. In some ways, I realized, my whole project had been flawed from the start—to write a short story that intentionally put to work the ideas covered in Saunders’ book. Here was Saunders, all but confirming this.

Perhaps what we (those of us in the Saunders camp) hope for is that the study of craft and rigorous reading will create a subconscious awareness that will be activated as we write—ostensibly without plan, without intention. Even in revision, while we may be able to make big-picture diagnoses about the ways our drafts go wrong, I’m not sure we can impose a plan of action even at that point. We must continue to fumble our way through the dark, writing into the story, rather than imposing it. We nudge the draft closer to what feels true and compelling—one sentence at a time.

***

I returned to the story today and deleted all my marginal notes. Then I worked my way through the story again, switching from first to third person, and as I went allowed myself to add a line here, or push a thought further there. They were small changes that nonetheless felt freeing, and I felt the draft inching in a new direction. I imagine next time I’ll do the same. And the next time, and again. Gradual changes here and there and here and there, until the character reveals herself, and until the meaningful action reveals itself. At various points I may remind myself, a la Saunders, toask, Does this detail need to be here? How does it serve the story? and cut it.

The story may not be done for a while, so I’ll leave you with this passage from Saunders that, for me, reinforced my renewed acceptance of the long, ongoing process we must commit to in our development as writers. What we’re ultimately nurturing in is our own, unique relationship with our readers, that something only we can offer, a reason the world might need my voice, not necessarily instead of, but alongside others’. A reason to persevere.

“When I was a kid I had this Hot Wheels set: lengths of plastic tracks, metal cars, a couple of battery-powered plastic “gas stations.” Inside each station was a pair of spinning rubber wheels. The little car went in, then got shot out on the other side. If you arranged the gas stations right, you could urge a little car into one as you left for school and come back hours later to find the car still going around the track.

“The reader is the little car. The writer’s task is to place gas stations around the track so that the reader will keep reading and make it to the end of the story. What are those gas stations? Well, manifestations of writerly charm, basically. Anything that inclines the reader to keep going. Bursts of honest, wit, powerful language, humor; a pithy description of a thing in the world that makes us really see it, a swath of dialogue that pulls us through it via its internal rhythm—every sentence is a potential little gas station.

“The writer spends her whole artistic life trying to figure out what gas stations she is uniquely capable of making….Of all the questions an aspiring writer might ask herself, here’s the most urgent: What makes a reader keep reading? Or, actually: What makes my reader keep reading?“